A Short History of the Martini

Take the evolution of music. A succession of colourful geniuses (Beethoven, Hendrix, MC Hammer), unexpectedly leapt from tradition and forged new paths for others to follow.

But of course that’s not the whole story. If an unremembered bod hadn’t come up with the sustaining pedal, then no Midnight Sonata. No electric guitar, no rock ’n’ roll. No Vox distortion

pedal, no face-melting Hendrix solos. And without the Korg synth, what would we all be dancing around to at cheesy 80s nights? The history of music has more to do with technology geeks than tortured souls lamenting lost loves or glory-grabbing TV throwers.

The evolution of cocktails is much the same. Ask any bartender worth their celery salt about the origins of your drink and you’ll hear tales of maverick barkeeps, infamous barflies (usually Hemingway), glamorous Hollywood sirens, gamblers and gunmen. The truth is inevitably both murkier and more mundane. Origin moments weren’t often recorded because they weren’t that big a deal (weirdly, mixing the first Manhattan wasn’t deemed as significant a contribution to humanity as discovering penicillin). And many of the seemingly revolutionary leaps of imagination would have been so apparent that they may well have happened in multiple places at the same time.

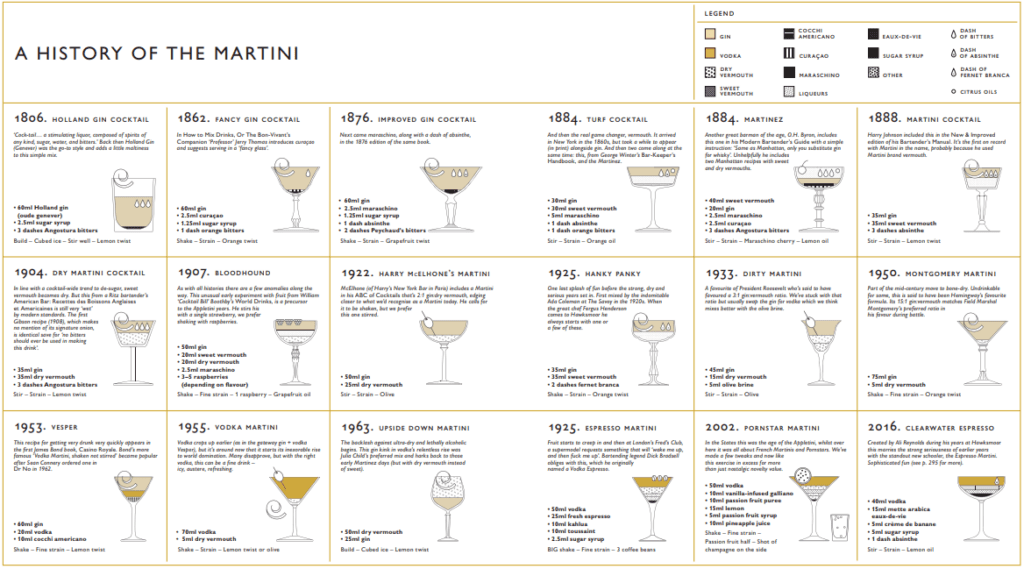

The history of the Martini also has more to do with the availability of ingredients than with creative geniuses behind the bar. As fancy new liquors arrived from distant shores, America’s bartenders welcomed them with open arms. A grateful benefactor was the decidedly dull Gin Cocktail (gin, sugar, water, bitters). As refrigeration improved, ice replaced water. And as new sweeteners arrived, people tried using these instead of sugar. First, it was fancified, then improved, and then vermouth came and its life changed forever. The first Martini-like drink was more an inevitability than a momentous discovery.

Over time a generous glug of sweet vermouth became the merest hint of dryness, and it became the strong, serious drink of Mad Men and secret agents. Until things went a bit Austin Powers. Thanks mainly to superior marketing budgets, and the genius of those Don Draper types, pretty-much tasteless vodka got involved, and before long people started ditching vermouth for flavoured liqueurs and syrups to add a bit of interest back in. To the tune of Stock, Aitken & Waterman murdering pop on the radio, bartenders churned out their overblown, sickly sweet concoctions. Among them, though, there were a few moments of sheer brilliance (all hail the Espresso Martini!).

“Muddle ¼ of a fresh banana (peeled), add 1½ shots of vanilla vodka, ¾ of a shot of butterscotch schnapps, ¾ of a shot of crème de banane liqueur, 1 spoon of maple syrup, ½ a shot of milk and ½ a shot of double cream. Shake with ice and strain into a martini glass.” Banoffee Martini, created by Barrie Wilson, 2003

The first Martini-like recipes were quite different. In his The Modern Bartenders’ Guide of 1884, O. H. Byron lists a drink called a Martinez with the simple instruction: ‘The same as the Manhattan, only substitute gin for whiskey.’ His Manhattan No.1 recipe was two parts sweet vermouth to one part whiskey. Sweetening gin with vermouth marked the end of the evolution of the Gin Cocktail – which had been first sweetened with sugar, then ‘fancified’ with curaçao and ‘improved’ with maraschino – and the start of the evolution of the Martini.

Byron’s drink would have been surprisingly sweet, for it to become something closer to the Martini we know today it needed to dry out. As well as the sweet vermouth he called for, the gin he would have expected his readers to use would have been the sweetened Old Tom Gin, the most popular style of gin in the nineteenth century. Just after he published his recipe, though, tastes started to change. Dry champagne (which had also to that point been sweet), dry gin and dry cocktails became the order of the day, leading a bartender to exclaim ‘No one but a fool or a farmer has his drinks sweetened’ (Spirituous Journey II, Jared Brown and Anistatia Miller, 2009). So the Old Tom Gin became the London or Plymouth dry and sweet Italian vermouth become dry French vermouth.

Then apart from adjusting the ratios (more gin, less vermouth), all that was left to add was an olive. And, thus, the Dry Martini was born. As the twentieth century progressed the amount of vermouth used was reduced until some, like Winston Churchill, decided to leave it out altogether. Churchill was said to have bowed in the direction of France when making his one hundred per cent gin Martinis instead. We can see the appeal of an ice-cold gin (or vodka) with the merest hint of vermouth, preferably with an olive or three in it, but our preference is for an old-style ‘wet’ – as it’s oxymoronically known in the trade – Dry Martini (a Martini with a decent slug of dry vermouth). Our preferred ratio? Five parts gin to one part dry vermouth (we use Noilly Prat) and, as a few early cocktail books suggest, a dash of orange bitters and a twist from the best lemon you can find (preferably a giant one from Sicily).

Towards the end of the century, things went a bit surreal for the poor Martini. On most cocktail lists neutral vodka replaced the more characterful gin and all sorts of flavourings were added, to the point that the non-Martini ‘Martini’ has become the defining drink of our age.

For martini purists James Bond’s ‘shaken not stirred’ is an outrageous faux pas. They side with Somerset Maugham who said that ‘martinis should always be stirred, not shaken, so that the molecules lie sensuously one on top of the other’ (whatever that means), or, even more bizarrely so as not to ‘bruise the gin’. The two methods do result in slightly different drinks and more often than not we’ll opt for the stirred version, but occasionally we prefer them shaken (gin or vodka). It makes for a colder, more diluted and slightly less serious drink that tends to slip down a bit quicker. Just the job if you’ve spent the day karate-chopping henchmen and pleasuring ladies.

After a tumultuous history, what will the future hold for the Martini? From the orders we’re getting over the bar, it looks like we’re coming full circle. More and more people seem to be enjoying proper old-school Martinis – perhaps the days of the Banoffee Martini are numbered.

Meet our current martini list here.